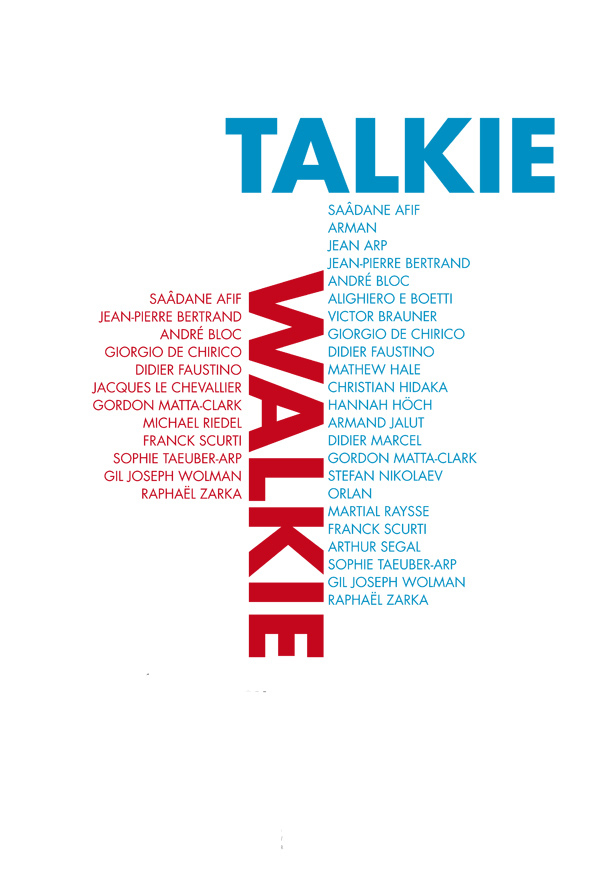

Talkie Walkie

June 8th - July 27th, 2013

Michel Rein, Paris

Installation views

About

Call it what you like: "ping-pong", "elective affinities", "an exchange of favours", "tit-for-tat", "collusion" or even "Walkie-Talkie". Whatever you think, this exhibition is ultimately less about the relationship with oneself, but an in-depth dialogue. The two galleries involved have known and understood each other for a long time, each from their own bank of the Seine: Natalie Seroussi on the left bank, and Michel Rein on the right. Each has their own specialty too, being modern art and contemporary art respectively. There is no level of competition, but each takes pleasure from sharing their strengths, playing their trump cards, playing by empirical rules, during a game of cards, during an exhibition.

The link between the two is Didier Faustino. Like a genie out of the lamp, this artist and architect has worked with Galerie Michel Rein in recent years. Over winter, drawn by his admiration and passion for the radicalism of artist-architect Gordon Matta-Clark (in terms of his aesthetic, politics, and plastic work), Faustino accepted an invitation by Natalie Seroussi to design an exhibition of photographs about the architectural sculptor, who died in 1978.

Just as Faustino redesigned the Michel Rein gallery, after "Walkie-Talkie", he will completely overhaul Natalie Seroussi’s space. Building on their first exchange, this is a sign of this woman’s commitment to stimulating new dialogue between contemporary art, and the modern art that she is so talented at displaying.

It took a lot of patience and goodwill in order for these two consummate professionals and their genie to come together at the right time. Organising their respective agendas was somewhat harder than matching their will. In the end though, each was able to play their cards, dig their historical treasures out from here and there, stand-up for the beloved pieces, and disclose their rarities. Natalie Seroussi was guided by her architectural loves, which underpin the tight selection of twelve artists and architects. This selection has been necessarily subjective, or especially subjective, I would even say. In this kind of exercise in style, what makes an exhibition interesting is its eclectic styles. It says much about the author-selector. Natalie Seroussi was rational. Michel Rein was overwhelmed by his lust for the selection of modern marvels that were offered to him. It must be said that "his" artists have a certain historiographical scholarship that is well-suited to the grand masters imported by Natalie Seroussi. There are more than double the number of works at his space on Rue de Turenne. The gallery is also larger. But aside from this, another reason for his appetite was his personality. Michel Rein’s team might not have followed his fellow gallery owner’s lead by sticking to a theme, but they have managed to impose a sense of visual coherence through reviewing the forces at play.

Take for example the fetishes or totemic forms that can be seen in Babel (Shambles), (2010), the composition of white boxes by Saâdane Afif, in Prismatique (P3), 2012, Raphaël Zarka’s oak and concrete composition, in the ghostly tree trunk signed by Didier Marcel (Colonne (hêtre), 2010), in Dead Domesticity Zone (Redux), the skull made from carpet created by Didier Faustino last year, or in the mask "à l’africaine", which Franck Scurti made from thermoformed plastic (White Memory F, 2007). Each of these contemporary 'arguments' respond to Composition horizontale –verticale, a geometric watercolour painted in 1916 by Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the luscious and delicate pristine plaster by Jean Arp (Propriétaire du tonneau de Heidelberg, 1962), or the dissonant associations of the collage Aus der Sammlung: Aus einem Ethnographischen Museum, No. IX, made in 1929 by Hannah Höch. One could write a narrative about these few works, based on their visual, formal, and especially intellectual affinities, which were obvious to the gallery curators that selected them.

Museum exhibitions are almost always conceived based on a selection that is well tested, thematic, monographic or chronological. In recent years, art centres have been tempted to encourage artists to take responsibility for the subjectivity of their choice. This freedom is not always taken on by the curators, who are made to act like authors – as if this is an important word! In a gallery, freedom is left up to the owner. If they want to "make" the authors, they can. Natalie Seroussi and Michel Rein might not have not been left deprived by having their "stories" cluttering up the works. Of the 12 participants selected by the galleries, eleven are shared between the two. But they do not share the same affinities.

Love Me Tender (2000), Didier Faustino’s sadistic chair that gleams with devilish beauty, shares the space with three constructionist lamps of aluminium by Le Chevallier (1920), a photograph of Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural deconstruction (Conical Intersect, 1975), and Off the Grid, which is a worksite grill recovered and then plated with gold and boa skin by Franck Scurti in 2013. The space becomes a conceptual proof that creates more than just a formal acquaintance between the works, but instead provides an artistic orthodoxy that is a mainstay of the works. And it's almost a happy ending when Natalie Seroussi offers a metaphysical drawing by De Chirico from 1917 next to the delicate Forme à Clé, which Raphaël Zarka photographed on the same palette of the Italian painter in the latter’s studio. To be clear, this exhibition has not been designed by accident, but rather by powerful intuition.It has taken the eyes of two galleries to develop this dialogue, which is like sending smoke signals from one side of the river to the other, in codes that are specific to each and indecipherable to the everyman. But in the end, in the beauty of this gesture we find understanding. For what fulfils the interest of this game is that it leaves its place and responsibility to the visitor, who can never be in both places at the same time. The spectator will be forced to see, to leave, to forget, and to remember, as they leave one to reach the other, or be satisfied with just one half. I myself have done nothing more than play a part with the notes of others, but the little music that comes out belongs to me. This is the gift that “Walkie-Talkie" offers to its visitors: that of inviting them to create dialogue.

Bénédicte Ramade